Sharing notes from my ongoing learning journey — what I build, break and understand along the way.

Kubernetes Explained: From Monolith to Microservices, Docker Containers, and Kubernetes Architecture

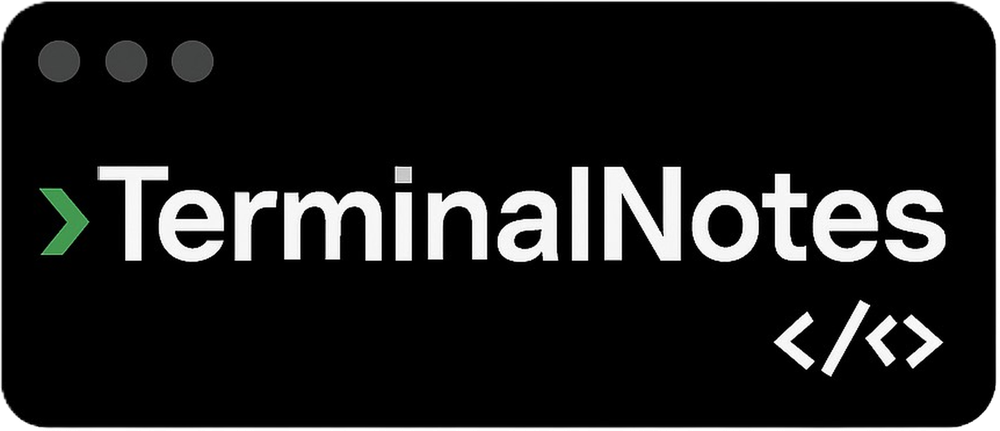

The Evolution of Software Architecture: Monolith → Microservices → Docker → Kubernetes

CHAPTER 1: THE EVOLUTION OF SOFTWARE ARCHITECTURE AND THE MICROSERVICES REVOLUTION

To understand Kubernetes, you first have to understand the world it was designed to manage—namely, the Microservices Architecture. Because Kubernetes wasn’t invented for old-school systems; it was invented for next-generation distributed systems.

So why did this change happen? Why did we abandon the old methods?

1. STARTING POINT: MONOLITHIC ARCHITECTURE (ONE SINGLE PIECE)

Before 2010 (and still in small projects), software was designed in a “Monolithic” way. Monolith means “a single block of rock.”

1.1. What is a Monolith?

Think of an e-commerce site (e.g., what Amazon looked like 15 years ago). Every task on this site:

- User login

- Product search

- Add to cart

- Take payment

- Issue an invoice

…all of it lived inside a single project folder, a single codebase, and ran on a single server. Everything was tightly coupled—like a gigantic, single-piece wedding cake.

1.2. The Deadly Problems of the Monolithic Structure

As things grew, this structure became sluggish, and the following crises appeared:

- Domino Effect (Single Point of Failure):

If a developer makes a tiny coding mistake in the “Invoice issuing” module, it doesn’t just break invoicing—the whole site goes down. Because everything shares the same memory and the same process. If the payment system is broken, the user may not even be able to log in. - Fear of Updates:

Adding a new feature to the site (for example, a “Add to Favorites” button) becomes a nightmare. When you change code, the risk of breaking some other part of the system is very high. That’s why companies used to say, “We only deploy updates twice a year.” There was no speed. - Technology Lock-In:

If you wrote the project in Java 5 years ago, you are forced to continue with Java forever. You can’t say, “Let’s write this new module in Python and use AI.” A single rock demands a single material. - Scaling Waste (The Most Critical Point):

This is very important. Let’s say Black Friday arrives and only the “Payment System” is under heavy load. Other parts (Product reviews, Blog, etc.) are calm. In a monolithic architecture, you can’t multiply only the payment part. You must copy the entire massive site (the whole cake) and deploy it to new servers. For a mere 10% hotspot, you consume 100% server resources. That’s an incredible waste of money.

2. THE SOLUTION: MICROSERVICES ARCHITECTURE (BREAK IT APART AND MANAGE IT)

When giants like Netflix, Amazon, and Google started suffocating under these problems, they said: “Let’s break this single block of rock. Let’s write small, independent mini-programs that each do one job.”

That is Microservices.

2.1. What is a Microservice?

They took the old “Giant E-Commerce Application” and split it into 50 small applications:

- Login Service: Only checks username/password. Does nothing else.

- Product Service: Only lists products.

- Cart Service: Only handles adding to the cart.

- Payment Service: Only talks to the bank.

These small programs (Services) talk to each other over the network (through the “telephone lines” we call APIs). When a user enters the site, in the background it’s actually 50 different programs running at the same time and responding to them.

2.2. Why Microservices? (Advantages)

Why do companies go through all this trouble?

- Freedom and Speed:

The team developing the “Payment Service” is independent from the other teams. They can deploy whenever they want. There’s no need to shut down and restart the whole site. Netflix deploys thousands of times a day—and you don’t even notice. - Fault Isolation:

If the “Product Reviews Service” crashes, only reviews disappear. The site continues running and selling products. The ship doesn’t sink—only the light in one cabin goes out. - Technology Diversity (Polyglot):

The payment team says, “We’ll use Java.” The AI team says, “We’ll use Python.” The frontend team says, “We’ll use Node.js.” In microservices, this is possible. Everyone speaks the language they know best. - Efficient Scaling:

Back to Black Friday: only the “Payment Service” is busy? Then you spin up 100 more copies of only that service. Other services (Blog, Contact) stay at 1 copy. You don’t pay for unnecessary servers.

3. THE NEW PROBLEM: COMPLEXITY AND CHAOS

Microservices sound great, right? But there’s a price.

Before, you dealt with one giant monster (the Monolith). Now you’re dealing with 100 little mischievous kids (Microservices).

This is where the system administrators’ nightmare begins. The problems are:

3.1. The “Which Service Is Where?” Problem

You have 100 services. You distributed them across 20 servers.

- “Cart Service” is currently running on which server? What’s its IP address?

- Service A wants to talk to Service B, but B’s address keeps changing. How will A find it?

3.2. The “Application Incompatibility” Problem

- Service A wants Java 8.

- Service B wants Java 11.

- Service C wants Python.

If you try to install all of them on the same server, libraries collide (Dependency Hell). If you open a separate server for each service, you go bankrupt.

4. INTERMEDIATE SOLUTION: THE CONTAINER (DOCKER) REVOLUTION

To solve the “incompatibility” problem created by microservices, Containers (Docker) were invented.

We can understand this through the logistics industry. In the past, cargo was loaded onto ships randomly. A sack of flour ended up on top of a car; a crate of tomatoes got crushed under furniture. Then the standard shipping container was invented.

- It doesn’t matter what’s inside (car or tomatoes).

- Its external dimensions are standard.

- Every ship, every crane, every truck can carry it.

Docker is the shipping container of software. A developer puts their microservice (whether Java or Python) into a box and closes the lid. As an admin, you don’t care about what’s inside the box. You only know how to run that box on a server. This ends the “It worked on my machine” problem.

5. THE GRAND FINALE: WHY KUBERNETES? (THE NEED FOR ORCHESTRATION)

Now we have all the pieces:

- Hundreds of tiny, split-up applications (Microservices).

- Each one packaged inside boxes (Docker Containers).

But there’s still a huge missing piece: Who will manage these boxes?

Imagine a scenario: It’s 03:00 at night. In your company, 500 microservices (containers) are running.

- Server number 3 suddenly burns out and shuts down.

- That server contained “Payment Service” containers.

- Customers can’t pay right now.

If Kubernetes Didn’t Exist:

You would have to wake up, log in, check “Which server has capacity?”, and then manually restart the “Payment Service” boxes (containers) one by one. While you do that, the company would lose millions of dollars.

This is where Kubernetes enters the stage.

5.1. Kubernetes What is it? (Metaphorical Definition)

Kubernetes is the Port Operator of these container boxes (the Orchestra Conductor).

You only give Kubernetes a wish list (a Manifest):

“Hey Kubernetes! For my ‘Payment Service’, I want 3 instances running at all times, no matter what. For my ‘Cart Service’, I want 2 instances running.”

Kubernetes receives this order:

- It looks at the servers, finds free space, and places the boxes.

- Observe: It constantly watches with binoculars: “Are 3 payment service instances running?”

- Intervene: If a server burns down and the number of Payment Service instances drops to 2, it spins up the 3rd copy on another server within milliseconds—before you even wake up.

5.2. In Summary: Why Do We Need It?

New systems need Kubernetes because:

- Manual Management Is Impossible:

You can’t manage hundreds of moving parts (microservices) by human hands. You need a robot (automation). - Zero Tolerance for Downtime:

Customers do not accept “The site won’t open.” Kubernetes keeps the system standing at all times (High Availability). - Cost Savings:

It fills server resources as efficiently as playing Tetris, preventing you from paying unnecessary electricity bills.

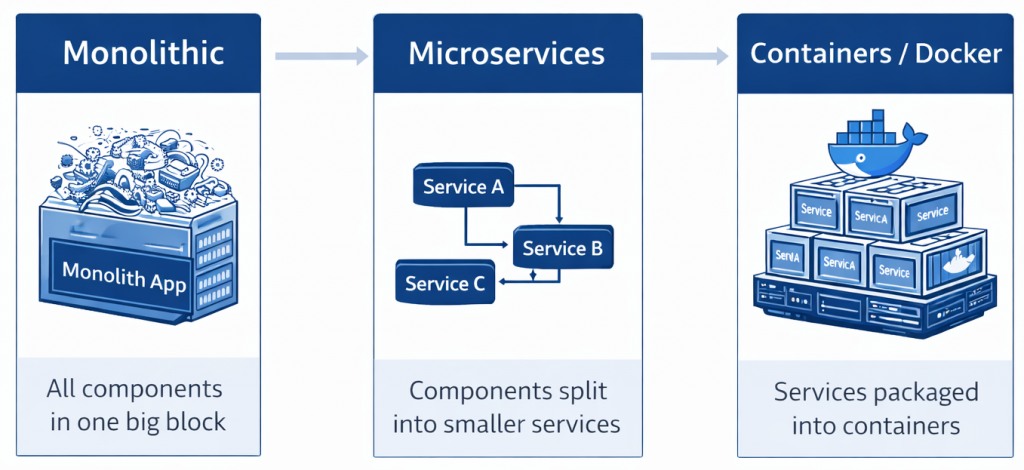

CHAPTER 2: THE ENGINE UNDER THE HOOD (TECHNICAL ARCHITECTURE)

Now that we answered “Why Kubernetes?”, we can move on to “What is Kubernetes and How does it Work?

Don’t think of Kubernetes as a single-piece software (like Word or Excel). Kubernetes is a distributed system made of many components that communicate with each other. Let’s examine this system using the metaphor of a construction site or a fleet of ships.

The system is divided into two main layers:

- Control Plane (Management Layer): The Brain Team where decisions are made.

- Worker Nodes (Work Nodes): The Muscle Power where the work happens.

6. KUBERNETES ARCHITECTURE: BRAIN AND MUSCLES

6.1. Control Plane (Brain Team / Master Node)

This layer is the captain’s bridge of the cluster. Your applications (website, database) do not run here. This is only the command center.

A. API Server (The Gatekeeper)

It is the heart of the Kubernetes architecture. It is the only gateway to the outside world.

- When you run a command (

kubectl apply...), that command does not go directly to servers. It goes to the API Server first. - The API Server checks your identity (“Are you an admin?”), validates the request format, and if it accepts it, it processes it. All other components talk only to the API Server.

B. etcd (Memory / Black Box)

This is Kubernetes’ memory. Every kind of information in the cluster (How many pods on which server? What are the secrets? What are the settings?) is stored here.

- etcd is a very critical Key-Value database. If etcd is deleted, Kubernetes loses its memory and forgets who was assigned to what. That’s why etcd is the most critical piece in backup strategies.

C. Scheduler (Logistics Manager)

When a new job (Pod) arrives, this is the algorithm that decides on which server (Node) it will run.

- While deciding, it checks things like: “Node-1 RAM is full, Node-2 is empty. Then send this job to Node-2.”

- This is the automatic solution to the “Bin Packing” problem.

D. Controller Manager (The Inspector)

This is the “Guardian” of the system. It constantly patrols.

- Its job is to find the difference between the Desired State and the Current State.

- Example: You said “There should be 3 web servers.” The controller checks and sees there are 2. It immediately tells the API Server: “One is missing—start it now!”

6.2. Worker Nodes (Workers / Muscle Power)

These are the servers where customer-facing applications (microservices) actually run. They can be virtual (VM) or physical (Bare Metal).

A. Kubelet (Foreman)

An agent running on every worker server (Node).

- Like the chief in a ship’s engine room. It listens to orders from the API Server (the Captain).

- It says: “I was told to run this container,” and passes the command to Docker (or containerd).

- It checks whether the container is alive and continuously sends reports (heartbeats) back to the center.

B. Kube-Proxy (Traffic Police)

Manages network traffic inside and outside the server.

- Routes incoming requests from customers to the correct container.

C. Container Runtime (Engine)

The engine that actually does the work: the software that pulls and runs containers (Docker, containerd, CRI-O).

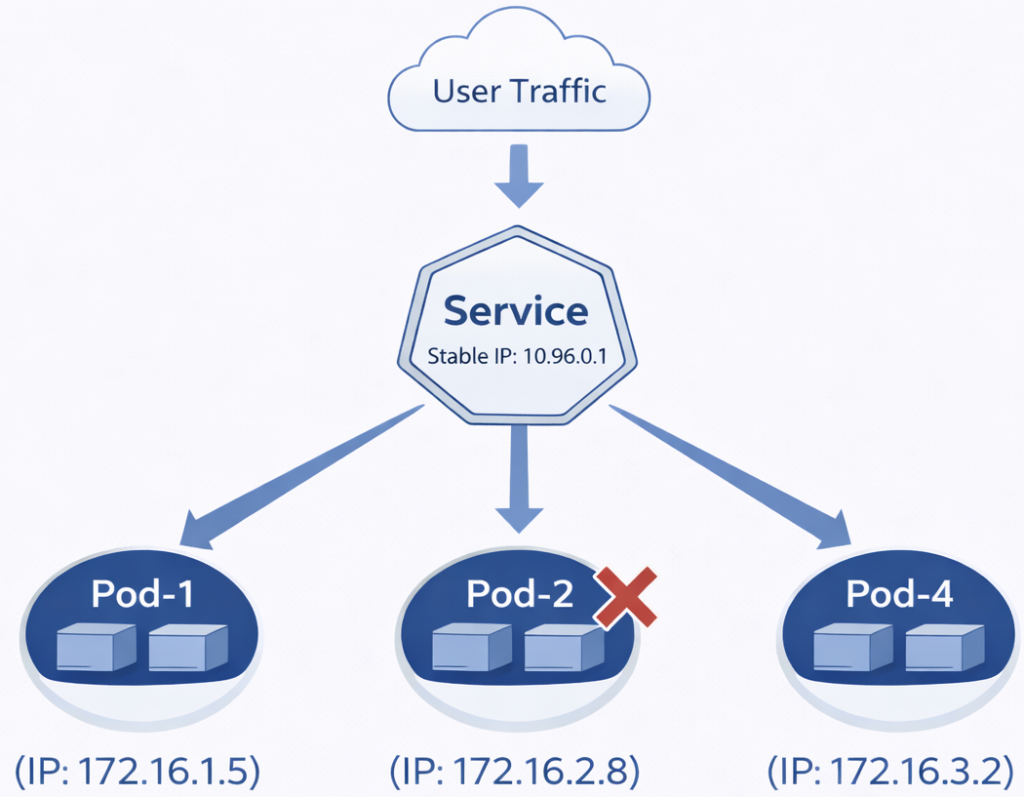

7. KUBERNETES DICTIONARY: OBJECTS

Kubernetes does not manage Docker containers directly. It wraps them inside its own special packages. These famous terms are what solve the conceptual confusion:

7.1. Pod (The Smallest Unit)

This is very important: In Kubernetes, the smallest building block is not the container—it’s the Pod.

- What is it? A “shell” around one or more containers.

- Why does it exist? Sometimes two containers must work like “conjoined twins.” (Example: one is the main application, the other is a helper that collects its logs.) We put them in the same Pod so they can share the same IP address and disk.

- Property: Pods are ephemeral (short-lived). When a Pod dies, Kubernetes doesn’t repair it; it throws it away and creates a new one. That’s why you should never trust Pod IP addresses—they constantly change.

7.2. ReplicaSet (The Replicator)

We don’t create Pods one by one manually.

- Logic: We say: “I always need 3 copies (replicas) of my ‘Payment Service’ Pod.”

- ReplicaSet constantly checks the number. If one crashes, it starts a new one immediately.

7.3. Deployment (The Manager)

This is the object we use the most in production. It is also the boss of ReplicaSet.

- Its job is to manage application updates.

- Scenario: Your app v1.0 is running. You will move to v2.0.

- Solution: Deployment performs a Rolling Update. If you have 10 Pods, it first stops 2 and starts v2. If there is no problem, it proceeds with the next 2. The update finishes with Zero Downtime (without ever shutting the system down).

7.4. Service (Stable Address / Load Balancer)

We said Pods are constantly dying and being reborn; their IP addresses change. So how will other services or customers find that Pod?

- Solution: We put a Service in front of the Pod group.

- How does it work? The Service has a stable IP and a DNS name (e.g.,

my-service.local). Even if the Pods behind it change, the Service address never changes. It distributes incoming traffic across healthy Pods behind it.

8. HOW DOES THE MAGIC HAPPEN? (DECLARATIVE MANAGEMENT)

The biggest feature that differentiates Kubernetes from its competitors is the “Declarative” management approach. This completely changes the way a system administrator works.

8.1. Imperative (Old Style – Command Mode)

In the past, we would write a script:

- “Connect to Server 1.”

- “Download the application.”

- “Run it.”

- “If there’s an error, retry.”

This method is fragile. If one step gets stuck, everything stops.

8.2. Declarative (Kubernetes Style – Wish Mode)

In Kubernetes, we don’t say “How to do it”—we say “What we want.” We do this using YAML files.

Example Request (Manifest):

“I have an application called ‘Web-App’. I want 3 instances of it running at all times. And the image should be nginx:latest.”

We give this request (kubectl apply -f request.yaml) to the system and we don’t interfere further.

- Kubernetes checks: “Right now there are 0.”

- Target: “3.”

- Action: “Create 3.”

If one crashes at midnight, Kubernetes checks:

- Current: “2.”

- Target: “3.”

- Action: “Create 1 more.”

This Self-Healing loop is what lets system administrators sleep peacefully at night.

9. NETWORKING AND STORAGE (THE CAPILLARIES)

9.1. Networking

In the microservices world, network management is difficult. To simplify this, Kubernetes uses the “Flat Network” model.

- Every Pod inside the cluster can talk directly to every other Pod (even if on different servers) without NAT (Network Address Translation).

- To bring traffic from the outside world inside, we use Ingress, which are “Smart Routers.” (Example: “Send requests coming to

abc.comto Service A, and requests coming toxyz.comto Service B.”)

9.2. Storage

Containers are temporary; data inside them is deleted. So where do we put database data?

- Persistent Volume (PV): The external disk where data will persist (Storage, Cloud Disk, NFS).

- Persistent Volume Claim (PVC): The Pod’s “plug/claim ticket” to attach to that disk. Even if the Pod dies, the disk (Volume) waits safely aside. When a new Pod starts, it attaches to that disk from where it left off.

10. CONCLUSION: THE INFRASTRUCTURE OF THE FUTURE

To summarize: The software world evolved from huge structures that were impossible to manage (Monolith) to small pieces whose count can reach thousands (Microservices).

This evolution created a complexity that cannot be managed by human power.

- Docker solved the transport problem by putting these pieces into standardized boxes.

- Kubernetes built a massive Automation Factory that carries these boxes, places them, renews them when they break, and routes traffic.

As an IT student, learning Kubernetes is not just learning a new program; it is learning the operating system of modern IT infrastructure. In the future, we won’t manage servers one by one; we will entrust them to Kubernetes—and we will manage Kubernetes itself.